With this post, we introduce a new member of our blogging team, Kate Taylor, who recently joined The Yellin Center Team as a Clinic Coordinator. Welcome, Kate!

With the arrival of March comes the gentle reminder that spring and summer are close at hand. Soon, school will be out and kids everywhere will be looking forward to the happy months of summer vacation. But for teenagers, summer break is not just a time for fun--it can also mean getting a job, one of the first big steps into adult life.

Why is the first job such an important milestone? Most obviously, having

a job brings new financial responsibilities into your child’s life.

Teenagers gain a sense of independence and control over their own life,

as well as a physical reward for the benefits of hard work. A job is

also a great opportunity for some hands-on experience in money

management. Instead of monitoring or controlling your child’s wages,

allow them to explore the benefits of spending versus saving through

their own decisions. That doesn’t mean that you can’t offer budgeting

advice, or help them to set up a bank account. But control over their

own money helps your teenager to practice the saving and budgeting

skills that will be so important later in life.

Having a job also allows teenagers to expand their social networks and

develop their socialization skills. School environments can be very

close knit and structured. Behavior in school is dictated by strict

social rules that can be frustrating and constricting. Having a job is a

great first step for teenagers to expand their social networks outside

of the school environment. The teamworking skills that come along with a

job are also crucial. Whether they strengthen their friendship-making

skills, or they learn how to deal with prickly coworkers, your teenager

will definitely have the opportunity to fine-tune their socialization

skills. Furthermore, the hierarchical relationship between management

and employees can help your teenager to develop the social skills

necessary for dealing with authority figures.

When I first started working, my dad told me that the most important

thing you can do is show up on time. “Fifty percent of life is just

showing up,” he told me. Time management is one of the most important

things you learn when you start working. Managing this balance is doubly

important if your teenager decides to continue working during the

school year. Keep an eye on their grades to make sure that working is

not disrupting their academic career--at the end of the day, school

should always be prioritized over a job. Whether your child has to

schedule work around school, juggle two jobs, or organize their social

life around a job, the time management skills developed while working

are incredibly helpful later in life, especially if your child is

seriously considering college.

The benefits of a job are

extensive, but it is also important to recognize that a first job can be

overwhelming, and requires a lot of energy, both physical and mental,

from your child. As a parent, it is your job to prioritize your

teenager’s mental and physical well-being over any obligations to a

part-time job. Make sure the workplace is a safe one, whether that means

fully understanding the job tasks (working with machinery or in a

kitchen, for example) or the people in the workplace (helping your child

to recognize inappropriate behavior from supervisors or coworkers and

what to do if it occurs). Make sure your child is taking care of

themselves. Regular communication is important, especially if their job

requires any extended driving time. Shifts can disrupt mealtimes or

regular bedtime, so always check that your child is eating enough and

getting enough sleep. Also make sure that the job is not stopping your

child from having an active, relaxing social life with both family and

friends. There are going to be a lot of changes and adjustments when

your child starts working. Whether they need advice, comfort, or

support, be sure you are paying extra attention to their emotional

needs.

Official Blog of The Yellin Center for Mind, Brain, and Education

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

Wednesday, February 19, 2020

Managing Screen Time

Smartphones have revolutionized the world, putting an unprecedented wealth of resources at users’ fingertips. But many parents worry that the siren song of these alluring devices is a little too enticing. Research indicates that their concerns are well founded, like this study from Preventative Medicine Reports that found associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents; this study from JAMA Pediatrics that found a link between screen media use and lower academic performance among children and adolescents; this study from PLOS that documents a connection between screen time and inattention problems in preschoolers…. We could go on.

It seems like common sense that too much of anything isn’t good for anyone, yet young people are desperate for more time on their phones and tablets. So what are parents to do?

Apps that limit screen time are a great solution to this problem. After a discussion about family device policies, parents can set boundaries on kids’ technology use and then let the app itself be the bad guy, freeing them from having to monitor screen time and starting arguments when the limit has been reached.

New apps that will help control kids’ screen use crop up regularly. For now, here are a handful of current options that are worth investigating:

Free

Available on: App Store, Google Play

Moment quietly tracks pick-ups and screen time, then generates weekly reports. We like the feature that allows the app to send notifications about how a user’s daily performance compares with pre-set goals. The overall tone of the app is encouraging, not punitive. Of course, these gentle reminders will work only if the user in question is convinced that too much screen time is to be avoided. Moment doesn’t shut down devices, it just provides a snapshot of how much time is being spent on them. So, if learning that she spends seven hours a day on Snapchat won’t shock your teen, this may not be the strong-arm solution you seek.

Screen Time

Free

Available on: iPhone (it comes pre-installed)

This solution couldn’t be more convenient, though it’s easy for determined kids to change the limits they’ve set; you need buy-in from your child for this to work. Screen Time allows users to schedule time away from the screen in advance or limit the amount of time they spend on a particular app. Like Moment, Screen Time works best if your child agrees that limits on phone use should be in place.

OurPact

Free, with $2/month and $7/month upgrades

Available on: Google Play

This app does it all: controls screen time, blocks apps, locates/tracks the device, shuts down texts, etc. Kids can even navigate to a screen that shows them how much time they’ve got left for a given day, view the schedule for the week, etc.

Mobicip

$40/year for up to five devices

Available on: App Store, Google Play, Google Chrome, Windows, macOS

If your kid hops from device to device, Mobicip is for you. Using the cloud, this app tracks and filters use of apps and websites on both mobile devices and computers, keeping kids safe from questionable content and limiting the time they spend on screens.

Of course most experts seem to agree that there’s one important factor here that none of these apps include: good modeling by adults. Children whose parents are constantly buried in their own screens are likely to follow suit; after all, their parents are their first and best role models. So if you’re really worried about how much time your kids spend on their phones, be sure you start by taking a critical look at your own habits.

Wednesday, February 12, 2020

Strategies to Resolve Letter Reversals

Our last post looked at why children reverse letters when they write and how proper and consistent letter formation can help with this. Today, we share some other ways to help when children reverse their letters.

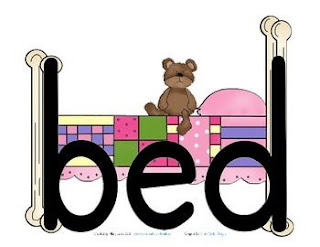

The "bed" Strategy

This simple strategy for recognizing and writing b and d give students an image to hold in their memories and a gesture they can make with their hands. Show your child the picture of the bed, emphasizing the /b/ sound when you point to the b and the /d/ sound when you point to the d. Show him how to hold his hands to make his own bed image. When he is writing and comes to a word that uses either b or d, ask him to look at the image (or, better yet, close his eyes and see it in his mind) or hold his hands in position to remind him which letter to use.

Recruit the Gross Motor System

Writing very large letters/numbers employs the gross motor system, strengthening a child’s memory for the sequences of movements needed to form letter and numbers. Kids think it’s fun, too! Using a wet sponge on a sidewalk, sidewalk chalk, a dry erase marker or chalk, challenge your child to write individual letters, numbers, or words that use problematic letters. You could also try “sky-writing,” in which a child uses her finger or whole hand to “write” in the air. Be sure she follows the sequence of motions she’d use to form the letters and numbers if she were using a pencil.

Make It Tactile

Feeling different textures can be useful in learning letter and number formation by underscoring the tactile experience of learning (rather than the largely visual experience that most children get). Your child can trace letters in a sand tray, on a piece of sandpaper, or on the carpet. He might also “write” in a layer of shaving cream spread on a table.

Another way to make letter formation tactile is to help your child form letters and numbers from clay or pipe cleaners. You could even use cookie dough and bake your child’s work – yum!

Make it Playful

This will sound familiar if you read our sight word posts. Your child might enjoy guessing games that require her to identify letters and numbers by how their shapes feel. A simple way to do this is to trace letters or on her back and ask her to say what has been written. She can also trace letters on an adult’s back for them to guess.

Another guessing game requires some set-up: Glue foam or wooden letters or numbers on pieces of card stock and add a line for the letter/number to sit on with a line of glue or puff paint (so that your child can feel which way the letter should be oriented). The cards can be put into a bag or box. With her eyes closed, ask your child to draw one out, feel it, and say which number/letter she is holding.

The "bed" Strategy

This simple strategy for recognizing and writing b and d give students an image to hold in their memories and a gesture they can make with their hands. Show your child the picture of the bed, emphasizing the /b/ sound when you point to the b and the /d/ sound when you point to the d. Show him how to hold his hands to make his own bed image. When he is writing and comes to a word that uses either b or d, ask him to look at the image (or, better yet, close his eyes and see it in his mind) or hold his hands in position to remind him which letter to use.

Recruit the Gross Motor System

Writing very large letters/numbers employs the gross motor system, strengthening a child’s memory for the sequences of movements needed to form letter and numbers. Kids think it’s fun, too! Using a wet sponge on a sidewalk, sidewalk chalk, a dry erase marker or chalk, challenge your child to write individual letters, numbers, or words that use problematic letters. You could also try “sky-writing,” in which a child uses her finger or whole hand to “write” in the air. Be sure she follows the sequence of motions she’d use to form the letters and numbers if she were using a pencil.

Make It Tactile

Feeling different textures can be useful in learning letter and number formation by underscoring the tactile experience of learning (rather than the largely visual experience that most children get). Your child can trace letters in a sand tray, on a piece of sandpaper, or on the carpet. He might also “write” in a layer of shaving cream spread on a table.

Another way to make letter formation tactile is to help your child form letters and numbers from clay or pipe cleaners. You could even use cookie dough and bake your child’s work – yum!

Make it Playful

This will sound familiar if you read our sight word posts. Your child might enjoy guessing games that require her to identify letters and numbers by how their shapes feel. A simple way to do this is to trace letters or on her back and ask her to say what has been written. She can also trace letters on an adult’s back for them to guess.

Another guessing game requires some set-up: Glue foam or wooden letters or numbers on pieces of card stock and add a line for the letter/number to sit on with a line of glue or puff paint (so that your child can feel which way the letter should be oriented). The cards can be put into a bag or box. With her eyes closed, ask your child to draw one out, feel it, and say which number/letter she is holding.

Friday, February 7, 2020

Letter Reversals

We are continuing our series of posts by Beth Guadagni, M.A., who teaches students with dyslexia in Colorado. Today, Beth looks at what happens -- and what teachers and parents can do -- when a child reverses letters.

First, let’s take a look at why reversals happen. During a young child’s life, he learns that an object seen from one side is the same object seen from another side. Whether he’s standing on the left or right of the blue armchair in the living room, it’s still the same armchair, even if the image appears to be reversed when he moves from one side to the other. When he begins school, he has to unlearn that concept; applied to letters and numbers, directionality can really change things.

This ability to appreciate mirror images is really useful—in most settings. On the page, it presents problems. Here are some ideas for helping your child:

Letter Formation – It Matters!

Watch your young child as he is writing and insist that he form letters the same way every time. This is particularly important with b and d. Many parents and educators skip this step, thinking that as long as the letter looks right in the end, how the child wrote it isn’t important. This is far from true. Remember:

- To make a lowercase b, the child should write the line first, starting at the top and moving downward. The loop is added next, so the letter takes two separate strokes.

- To make a lowercase d, the child should write the loop first. Then, without lifting her pencil, she can sweep upward to form the line, then down again for the tail.

We worked with a young boy whose insightful mother came up with a mnemonic to help him with b's and d's. When he wrote a b, he said “bat to the ball” to himself. The “bat” was the stem of the letter, which he had to write first. The “ball” was the loop. When he wrote a d, he said “dog to the door” to remind him to write the “dog” (the loop), then the “door” (the stem). This clever strategy marries the auditory and kinesthetic senses.

Resource: Handwriting Without Tears

If you’re worried about letter formation, we love Handwriting Without Tears. Its step-by-step instructions are easy enough for parents with no training in early education to follow at home.

Monday, February 3, 2020

Sight Words – Part Five: Games!

Tic Tac Toe

There are two variations of this game. Both begin with sight word flashcards face down in a pile. To play the simpler version, each player must draw a card and read it aloud before marking either an X or an O on the board. To make it more challenging, be sure each player has a pen in his own color. The first player will draw a sight word card and read it aloud to the other player. Instead of writing an X or O, the second player must spell the sight word in the square he chooses.

Fishing Game

There’s no competition here, but kids think this game is tremendously fun anyway. If you’re pressed for time, put a paperclip on each sight word flashcard. If you have time to really get into the theme, cut out simple paper fish and write a sight word on each, then slide a paperclip over each fish’s head. Put all the prepared words into a very large bowl or bucket. Now you need a fishing pole: tape a piece of string 18-24 inches long to a ruler and affix a magnet to the end. Give the pole to the child and show him how to dip the magnet into the “pond.” He should read the word on each fish he catches, then go back for more!

Memory

This old favorite is great for practicing sight words. You’ll need two sets of flashcards with sight words written on them. Eight to ten pairs seems to be a good number—fewer than that is too easy, and more than that is overwhelming. Mix the cards up and turn them face down, arrange them into a rectangle, and take turns looking for matches. Make sure each player reads the words aloud as he turns the cards over. For extra practice, when the game ends each player should read their cards aloud while counting them to determine the winner.

Go Fish

You’ll need quite a few sight words for this game - at least twelve - but the good news is you can use the pairs of cards you made for Memory. Give each player three or four cards, which he should keep hidden. If you’re using flashcards, these will be unwieldy to fan out in one’s hand like playing cards, so cut a file folder in half and give a piece to each player. The folder can be propped up in front of the player so that he can spread his cards in front of him in secrecy. The rest of the cards go face down between the two players. The first player should ask the second if he has a particular word. If he does, he must give his card to the first player. If not, the first player must “go fish” by drawing from the pile in the middle. The game continues until someone runs out of cards, and at that point the one with the most matches wins.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)